There’s something brewing in the whisky aisle. Join us as we decant.

Until about 15 years ago, the world’s largest whisky market (because that’s what we are) relied on imports for its tipple. Today, the awards are flowing in for homegrown brands, and India is drinking premium whiskies that don’t just shout that they’re Indian, they explain why that counts. (Read on to see how the climate and the barley here can actually make single-malts richer.)

Fifteen years is what it has taken, to move the needle.

“Indian whisky used to be equated with molasses,” says author and columnist Vir Sanghvi. “It was traditionally made by taking a neutral spirit (raw alcohol) made from a variety of sources — sugarcane and molasses in legend, but more likely rice these days — to which was added some kind of whisky flavouring, perhaps a real malt whisky. This was rarely aged for as long as Scotch, which is aged for at least three years, and usually for eight to 15. And so, when it hit the market, it was never as good as Scotch. But it was much, much cheaper.”

This was the stuff one drank in secret, as it were; when guests came over, one fished out an imported bottle. Because whisky has always been aspirational. It became popular in colonial India, among Indians looking to mirror the habits of the ruling British elite.

The whisky made by early Indian distilleries such as Piccadily in Punjab and Rampur in Uttar Pradesh were sought-after for their price, not their aged excellence, and so they used a mix of local grains and imported single-malt to produce “blended” whisky, light in flavour and impact.

All that changed with the launch of the Amrut single-malt in India, in 2010. Amrut Distilleries was already more than 60 years old at this point, but neither the brand nor indeed India had ever produced a single-malt: a pure, aged, rich whisky made from just barley.

In a perceptive move, this single-malt was first launched in Scotland, in 2004. By the time it came to India six years later, it was aspirational in an entirely new way.

It was unabashedly Indian (Amrut is Hindi for Food of the Gods). It was a recognised name overseas. It was winning awards, and thus certifiably good.

It was the whisky a younger, wealthier, post-liberalisation India had been waiting for. And it sparked a homegrown single-malt movement.

In 2012, John Distilleries, founded in 1996, launched Paul John. Rampur launched its eponymous version in 2016. The Indian arm of the British multinational Diageo launched an Indian-made Godawan (the Hindi name for the endangered Great Indian Bustard) in 2021; Piccadily launched Indri the same year. GianChand, founded in 1961, released its single-malt in 2022.

Indian brands now account for about 53% of total single-malt sales in the country, according to 2023 data from the Confederation of Indian Alcoholic Beverage Companies.

To us

It turns out, India has some unique advantages when it comes to single-malt production.

The climate affects both the barley and the ageing process in positive ways, allowing whiskies to age faster and emerge richer, says Sandeep Arora, whisky connoisseur, consultant, entrepreneur, and consulting editor at Whisky Magazine, UK.

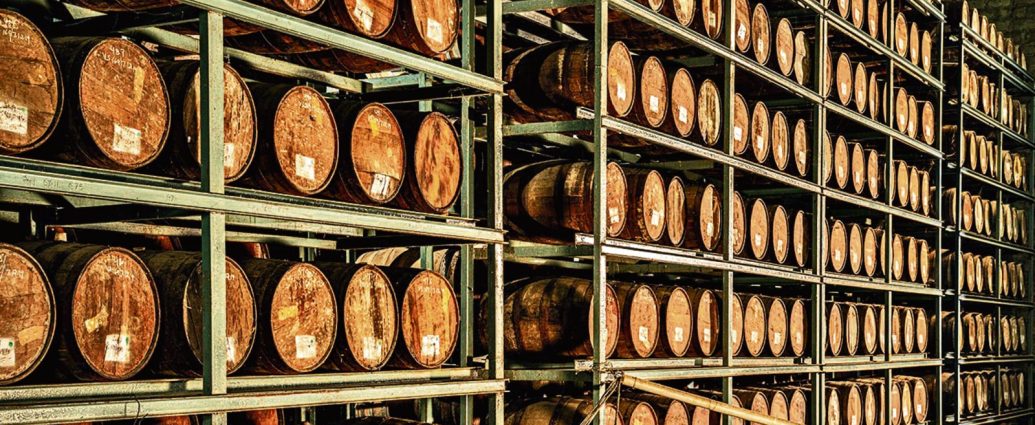

“In the northern plains of India, the temperature oscillates between zero degrees Celsius in winter and 50 degrees Celsius in summer, with just two months of rain and 10 months of dry weather. This extreme temperature makes the pores of a wooden cask expand and contract exponentially, making the interaction between the wood and whisky much more pronounced, thereby imparting far more flavours to the liquid in a short period of time,” says Siddhartha Sharma, CEO of Piccadily, whose Indri Dru variant won Best Indian Single Malt at the World Whiskies Awards this year.

The indigenous six-row barley has a higher protein content and a more robust husk than the two-row barley grown in Scotland and Japan (another major producer), says Vikram Damodaran, chief innovation officer with Diageo India. “This means that the Indian whisky has to go through extra layers of filtration, which result in less volume but a higher concentration of flavours.”

What’s the story?

We still need to find the narratives to go with the brands.

Stories have shaped premium single-malt brands worldwide. Scotland’s Glenmorangie prides itself on having one of the best distillers in the world. Japan’s Yamazaki boasts of using the country’s purest water. Glenlivet, the prestigious single-malt from Scotland, has an identity rooted in the unlawful distillation. It owes its smooth texture, the story goes, to the large copper pot stills it uses for distillation and maturation, which still resemble lanterns.

Beyond the barley and the climate, India is still finding its stories. Godawan, for instance, is made in Rajasthan and is working to revive ancient distillation processes there, including the slow-trickle method once used to make herbal liqueurs from spices such as saffron and cardamom, and flowers such as the rose.

The narratives will become vital as this massive market begins to draw a fresh wave of global attention.

Already, international giants are launching Indian-made brands. Godawan was an early mover. Last year, the French giant Pernod Ricard launched the made-in-Nashik Longitude 77 (named for the meridian that runs the length of India). Foreign brands are launching Indian-made blended whiskies too.

“What we are seeing is the beginning of a genuine domestic whisky-making culture,” says Sanghvi. “It will have an artisanal luxury segment, such as the small-production Diageo whiskies, as well as more mass-focused brands. And it will have different terroirs, just as Scotland has distinctive malts from different regions.”

Watch out for subtle notes of struggle, in the next few pours.