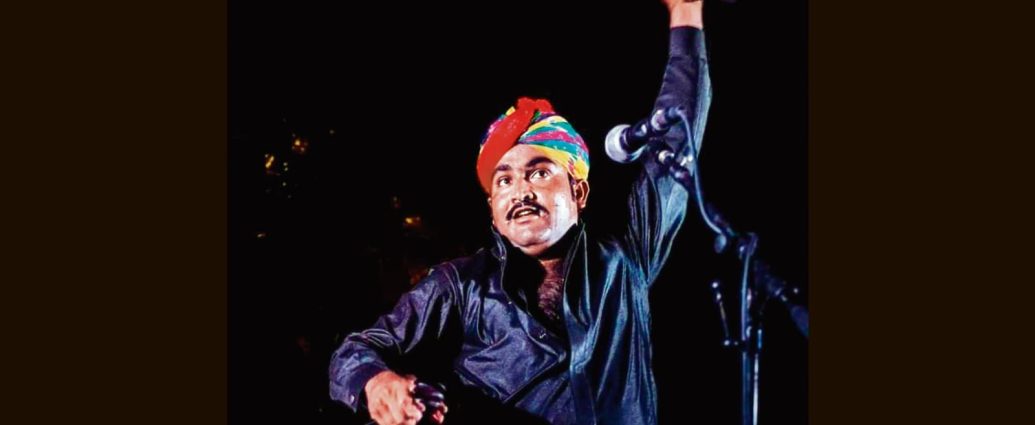

When the Manganiyar musician Rais Khan saw AR Rahman recording at a Mumbai studio in 2016, he remembers feeling overwhelmed. “I walked up to him and requested a photo. I was excited and in a great hurry,” says Khan, 35. Rahman told Khan to wait till he had finished his session.

Later, Khan took the mic, performing on his primary instrument, the Rajasthani morchang. (This unusual musical instrument is a small, metal, plucked device played with the mouth. It’s known in English as the jaw’s harp [also, Jew’s harp] and in southern India as the morsing, and has ancient roots in Asia.)

In the studio, Khan poured body and soul into his performance. “After it, Rahman Sir suggested that we take the photo together now,” Khan says. The track they worked on that day, Ranjha Ranjha Unplugged, was sung by Shruti Haasan and Rahman, as part of the reality TV show MTV Unplugged, with the sharp percussive twang of Khan’s morchang locking delectably with the groove of the drums and bass. It remains a testament to Khan’s versatility, his ability to seamlessly blend in, play foil and hold his own while negotiating with music starkly different from his own.

Khan has a new album out, and on it are more surprises. On the Rais Khan Project’s Folk Music for a Swasth India, he performs some rap, hip hop and beatboxing.

“If we don’t adapt and take it forward, Manganiyar music won’t survive,” Khan says, speaking from his village in Jaisalmer. Beatboxing, for instance, adds the resonance of dance music to a tune, while retaining the original structure and message of the art form. “I listen to all kinds of music and firmly believe that music is one big family.”

His vision for the near future is to achieve further musical inclusiveness. “I will be experimenting heavily with beatboxing, and incorporating music from around the world that I have been exposed to.”

In many ways, his versatility and open-mindedness have helped him to escape the boxes and prejudices that have sometimes accompanied the narrative of Rajasthan’s Manganiyar musicians.

New harmonies

The Manganiyars are a community of hereditary Muslim artists, largely from western Rajasthan, who have traditionally and for several centuries sung in groups on social occasions such as births or weddings in the families of their patrons, who were typically upper-caste Hindus. Their songs, rendered through strident vocals and the heavy use of percussion, are usually about Hindu deities and myth.

With the financial clout of their patrons diminishing over the years, many Manganiyars have taken to public spaces, performing for tourists at forts and palaces and sometimes at folk music and cultural festivals. Some have formed troupes to give themselves a better shot at booking events. In rare instances, artists such as Mame Khan have made solo careers as playback singers in Bollywood. Without patronage, however, much of the community has become economically marginalised.

Khan is a rare Manganiyar musician who has retained the essence of his traditional art form, continues to perform it independently, and is committed to reinventing it for the 21st century. He has brought his art form’s unique sound to EPs and has collaborated with folk musicians from around the world, including Grammy-winning English folk-rock act Mumford & Sons.

He has sung, as part of the Manganiyar ensemble Barmer Boys, with Algerian rai singer Khaled, Malian singer-guitarist Vieux Farka Toure and Nigerian Tuareg singer-guitarist Bombino. He has performed with the Copenhagen-based techno musician DJ Hvad, and the New York Gypsy All Stars. On the domestic front, Khan has worked with Amit Trivedi, Clinton Cerejo and Rahman, among others.

Fresh palates

It’s been a rough-and-tumble journey. Khan was forced to leave school in Class 7, after his father developed a psychological condition. At 13, he was suddenly heading a family and performing publicly to earn a living.

In 2009, at age 22, he was roped into The Manganiyar Seduction, theatre director Roysten Abel’s widely popular live music spectacle involving Manganiyar music that has enjoyed an impressive run across Indian and at global music festivals but has also been criticised for exoticising the art form. Then, unable to scrutinise his English contract with a record label, Khan says he spent 10 years tied to an exploitative agreement. He extricated himself from it with the help of friends from the industry.

It was then that he decided to only make the kind of music that made sense to him. He proceeded to explore collaborations in forms ranging from pop to jazz, Asian and Indian folk and electronica, working with artists from around the world. As he travelled, he struggled to swap meals of bajra rotis and dal-chawal for spreads of pizzas and falafel. “I found them difficult to eat,” he says, laughing.

Thirteen years on, he’s capitalising on a skill — beatboxing — that he learnt from the Australian musician Jason Singh in exchange for lessons in how to play the morchang. “I like falafel now,” he adds, laughing, “maybe more than certain Rajasthani dishes.”

This winter season, get Flat 20% Off on Annual Subscription Plans

Enjoy Unlimited Digital Access with HT Premium