The Museum of Art & Photography (MAP) is a landmark already, a long, sleek five-storey structure in the heart of Bengaluru. Two years after it was launched as a digital repository, in December 2020, MAP is readying to open the doors to its physical space in February. It celebrated, this past week, with a sneak peak of what’s to come.

Expect holograms, interactive displays, multimedia art galleries, and digital exhibits that allow you to zoom in on, and twirl, an ancient artefact. Also, a sculpture courtyard, research and conservation facility, auditorium, cafeteria, recreation hall and gift shop. Entry to the museum will be free (though certain exhibitions will be ticketed).

The preview, a three-day private ceremony held from December 9 to 11, showcased a set of exhibits from MAP’s extensive collection of over 60,000 artefacts ranging from sculpture and potshards to paintings, textiles and photographic art – all from across South Asia, going back to the 10th century CE.

The private museum has been founded by art collector Abhishek Poddar to study, promote and showcase work from the South Asian region. “I believe we need MAP now because South Asian cultures represent the cultures of nearly a quarter of the world’s population and yet their stories have not been told,” Poddar has said. “I hope that through the building, the collections and our online content, we can open up a dialogue with the world in this time when new narratives are being shaped.”

DIGITAL DNA

At the physical premises, art greets the visitor even before they get to the building. Sculptor Stephen Cox’s large, abstract basalt works lead up to the entrance lobby. Inside, at the Infosys Foundation Gallery on the ground floor, LN Tallur’s Chirag-e-AI, a collection of large stone, bronze, glass and plywood sculptures, offers commentary on our hyper-stimulated times.

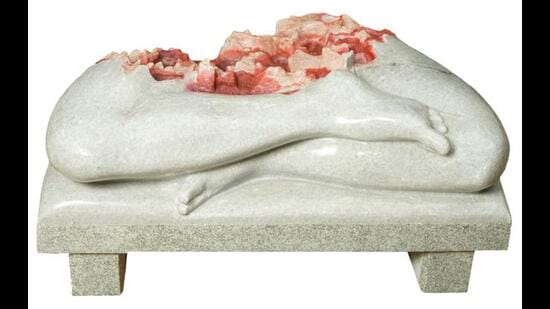

Two striking pieces – a white marble sculpture titled White Space, showing legs folded in the padmasana, with puddles of red ink collecting and seeping through the severed hip (above); and RNN (for “recurring neural network”), a giant Buddha head that appears to be rising out of a couch – illustrate the sense of being weighted down by the technology we have come to depend on and draw comfort from. “I wanted to use these pieces to talk about the tension between the human brain and the speed of computers,” Tallur says.

Upstairs, at the Jindal Stainless Steel Visual Storage Gallery, Poddar pops up to greet visitors. He’s not actually there. “Here at MAP we have created not only a space for all the beautiful art to reside in, but also a room for dialogue and canvas for creation,” says a hologram of the founder.

Moments later, an ancient clay pot appears where Poddar stood, suspended and spinning casually. Over 500 of the museum’s artefacts have been documented using photogrammetry, allowing them to be viewed as holograms.

“What’s interesting is because the entire structure is new, it’s built with digital technology in its DNA,” says Chris Michaels, digital director at the National Gallery, UK, who moderated a panel discussion on art and the digital revolution as part of the pre-opening. “And the technology is not about being cutting-edge. It’s about being honest and authentic in storytelling. The use of the holograms is not to make a sci-fi experience, but to show classical objects and to give you a very close-up view.”

On the second floor, artefacts that arrived in various stages of disrepair are on display outside the conservation centre. An oil painting by Sailoz Mookherjea (1906–1960), for instance, arrived covered in cracks. “We needed to examine it closer to determine the cause,” says conservator Paromita Dasgupta. A 300x view under a microscope revealed that a wax lining had once been used to restore the painting. Over time, and with changes in temperature, the wax softened and solidified, sending shockwaves all the way to the oil paint on the surface. The painting took a month to restore. “We used heat to melt the wax, then join and close the surface cracks,” Dasgupta says.

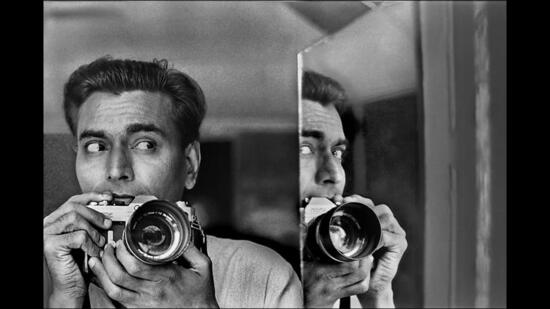

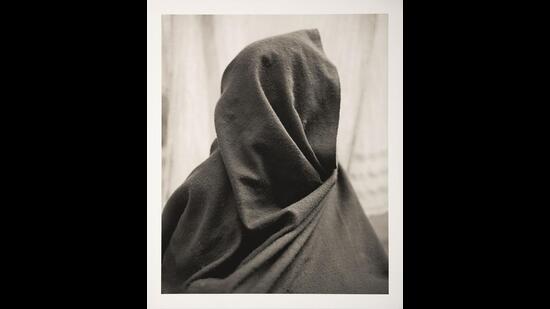

Onward and upward, at the Axis Gallery and Citi Gallery on the third floor, is a retrospective of one of the museum’s most sprawling collections, from the photographic archives of Jyoti Bhatt (1934-). Divided into three parts, Time and Time Again represents his three roles as a photographer – as a friend to people who would become some of the biggest names in Indian art, as a documenter of traditions and practices that were fast disappearing as a newly independent India modernised, and as an artist.

“We wanted to put a show together that would trace his journey and look at his experience with photography,” says Shrey Maurya, managing editor at MAP Academy, which works on MAP’s ambitious digital encyclopaedia of South Asian art, which went live this year. QR codes on some of the labels lead to entries in this compendium of 10,000 years of art practices and art forms in the region.

At the Manipal Gallery and Avanee Foundation Gallery on the fourth floor is another sprawling spread, and the museum’s star display – Visible / Invisible, a collection of modern, contemporary and classical art works chosen to represent women in art via the MAP collection.

Mrinalini Mukherjee’s fabric sculpture Naag (c. 1986) looms large over an etching by Bhupen Khakhar (Untitled, 1990s) and M Shantamani’s Reconstructing Venus (2004). Leather puppets show how female expressions of desire are chastised. Down the hall, Bengaluru-based artist Indu Antony’s exhibit features 21 photographs of the hairy legs of a grotesque and menacing uncle, viewed from the perspective of a child. Scattered around the two galleries of the Visible / Invisible exhibit are tactile displays for the visually challenged, and short films made in response to the art.

On the way out, light a lamp without fire. Visitors can scan the QR code displayed on giant screens on the ground floor, enter their name and, in keeping with the ancient-meets-modern theme of the space, choose a traditional brass lamp to light before they leave.

Enjoy unlimited digital access with HT Premium

Subscribe Now to continue reading