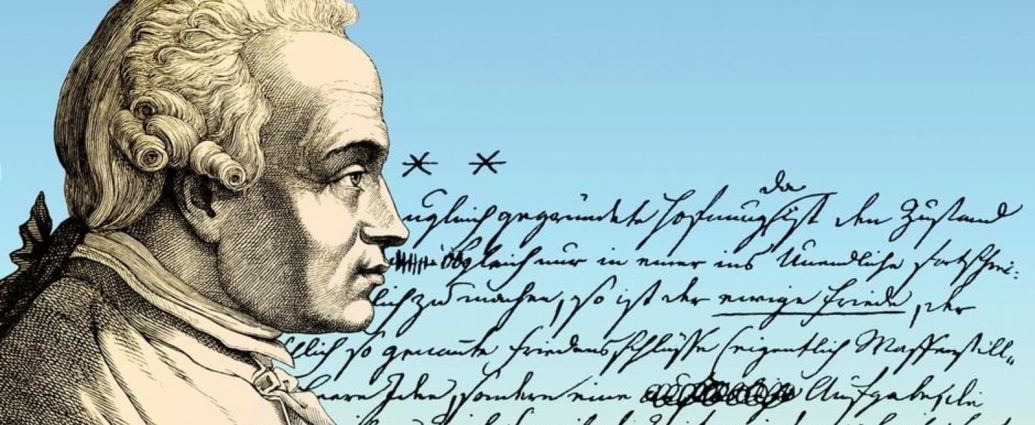

Anyone who relies on the voice of reason cannot ignore Immanuel Kant. April 22 marks the 300th anniversary of the German philosopher’s birth. What does the author of “Perpetual Peace” still have to say to us today?

If you want to understand the world, you don’t necessarily have to travel it. Take one look at Immanuel Kant (1724-1804). On April 22, the world celebrates the 300th anniversary of his birth. The German philosopher never left his East Prussian home of Königsberg — now Kaliningrad and part of Russia — yet this did not stop him from trying to understand the world. His ideas have revolutionized philosophy and made him a pioneer of the Enlightenment.

His most famous work, “Critique of Pure Reason,” is regarded as a turning point in intellectual history.

ALSO READ: Pursuit of peace in the shadow of war

Today, Kant is one of the most important thinkers of all time.

Many of his insights are still valid today, in the face of climate change, wars and crises.

For example, what could lead to lasting peace between states? In his 1795 essay, “On Perpetual Peace,” Kant recommended a “league of nations” as a federal community of republican states. According to Kant, political action must always be guided by the law of morality. His work became the blueprint for the founding of the League of Nations after World War I (1914-1918), the forerunner of the United Nations, in whose charter it left his mark.

In addition to international law, Kant also developed a world citizenship law. In doing so, he rejects colonialism and imperialism and formulates ideas for the humane treatment of refugees. According to the philosopher, every person has a right of visitation in every country, but not necessarily a right of hospitality.

In favor of reason and arguments

Kant does not justify human dignity and human rights religiously with God, but philosophically with reason. Kant had great faith in people. He believed they were capable of taking responsibility — for themselves and for the world. Kant believed that life could be mastered with reason and arguments, and formulated a basic rule for this — “Act in such a way that the maxim of your will could at any time be regarded as the principle of general legislation.” He called this the “categorical imperative.” Today we would formulate it like this: You should only do what is the best for all.

In 1781, Kant published what is probably his most important work. In “Critique of Pure Reason” he poses the four fundamental questions of philosophy — What can I know? What should I do? What can I hope for? What is the human being?

His search for answers to these questions is known as epistemology. In contrast to many philosophers before him, he explains that the human mind cannot answer questions such as the existence of God, the soul or the beginning of the world.

“Kant is not a light of the world, but a radiant solar system all at once,” German Romantic writer Jean Paul (1763-1825) said of his contemporary.

However, other intellectual greats found Kant’s writings difficult to digest. The philosopher Moses Mendelssohn complained that it took “nerve juice” to read them. He himself was unable to do so.

Pioneer of the Enlightenment

The teachings and writings of Immanuel Kant laid the foundations for a new way of thinking. Kant’s phrase “Sapere aude” (the Latin phrase meaning “Dare to know”) became famous and saw Kant become a pioneer of the Enlightenment. This intellectual movement declared human reason (rationality) and its correct use to be the standard for all actions. In his writings, Kant called for people to free themselves from any instructions (such as God’s commandments) and to take responsibility for their own actions.

Numerous judgments and prejudices still circulate about Kant today. The German philosopher and Kant researcher Otfried Höffe has put some of these to the test in his new book “Der Weltbürger aus Königsberg” (The world citizen from Königsberg), including the question of whether Kant was a “Eurocentric racist” or whether Kant discriminated against women.

The author shows that are nuances to the labels that are equally attributed to the German philosopher.

No couch potato

Kant was not a racist in the modern sense. On the contrary, he condemned colonialism and slavery. Although Kant never traveled beyond Königsberg, the capital of East Prussia was a vibrant trading city at the time, a “Venice of the North.” In addition, Kant had virtually devoured travelogues from other countries.

And was Kant a misanthrope? Although Kant had a strictly regulated daily routine, he enjoyed extended lunches with friends and acquaintances, loved billiards and card games, went to the theater and was considered a charming entertainer in the city’s salons.

Kant celebrations everywhere

Many events in Germany will commemorate Kant and his legacy in 2024, to mark 300 years since his birth. The Bundeskunsthalle in Bonn, for example, has been hosting a Kant exhibition named “Unresolved Issues.”

A major academic conference will be held in Berlin in June, followed by an International Kant Congress in Bonn in the fall, which was originally planned for Kaliningrad but cannot take place there due to the Russian war of aggression against Ukraine.

Kant’s grave adorns the back wall of Königsberg Cathedral. As one of the few historical buildings, the Gothic church survived the bombings of World War II and the subsequent wave of demolitions in the Soviet state.

Indeed, Kant’s impact on German legal history has been profound, but the rise of nationalism prevented his work from being the dominant force in German political thought until after World War II.

Now, 300 years on from his birth, Kant is still considered a prominent thinker, one capable of inspiring political movements to this day.