At 400 km from the surface of Earth, a very different rulebook for physics kicks in.

In the absence of gravity and oxygen, fire behaves differently, as does water. Materials acquire new melting points. Atoms clump together, in ways that hold new hope for quantum technology.

The International Space Station (ISS) has served as a laboratory for all this and more. How does the human body react to time in space? How can recycling systems be refined? Can plant life be supported off-planet (it turns out it can be, relatively easily; if one can find the water for it). Here’s a quick look at key ongoing experiments.

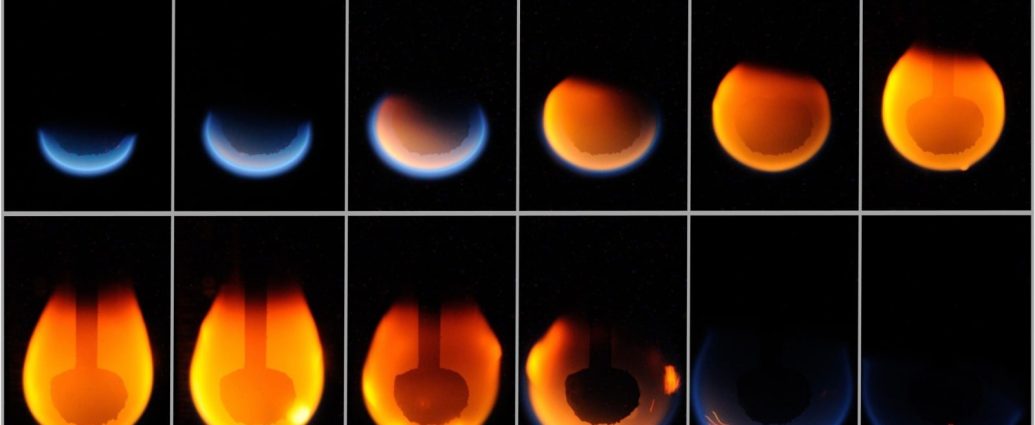

Fire: Thousands of flames have been lit in a series of experiments on board ISS, to investigate the underlying physics of flame structure and behaviour, from flame growth and decay to fire-extinction in space.

On Earth, gravity pulls cooler, denser air towards the ground, while hot gases rise, creating the classic shape of a flickering flame. In microgravity, small flames tend to be rounder. Experiments on ISS also led to the discovery of steadily burning cool flames, which burn at extremely low temperatures (a feat that is nearly impossible to accomplish on Earth).

“In the reduced gravity of space, fire can behave unexpectedly and could be more hazardous,” Paul Ferkul, a scientist at NASA’s Glenn Research Center, has said.

From spacesuits and spacecraft to habitats on the Moon or Mars, and power plants and boilers here at home, the implications are vast and varied.

Water: It has been intriguing and enjoyable for humans on Earth to watch water behave completely out of character on ISS. But how water behaves in space is also a perplexing problem that has implications for vital systems ranging from life-support to fuel tanks. Researchers are now studying exactly what causes water droplets to merge when and as they do. Answers wouldn’t just solve a long-standing mystery. They would help humans plan better, when it comes to storage, leaks and losses over years-long journeys.

Sleep: With no day or night, up or down, and multiple sunrises and sunsets in each 24-hour period, most astronauts on ISS have trouble sleeping. Two ongoing experiments are currently using fresh tools to seek solutions. The first, titled Circadian Light, uses a special lamp to simulate the calming reds of a sunset and blues of a morning sky, in attempts to induce more regular sleep cycles. The second, Sleep in Orbit, uses an in-ear device to measure astronauts’ brain activity through the night, with a view to assessing the quality of sleep, and finding ways to enhance it.

Planet monitoring: The space station offers a unique perspective across more than 90% of inhabited regions on Earth. A number of instruments on board monitor changes in oceans, air (and energy cycles), vegetation, geological hazards, seasons. Footage has helped track and assess the impacts of floods, wildfires, superstorms, tsunamis and volcanic eruptions. Images taken via the space station now form an archive of climate-change impact, as maps see their outlines shift.

A fifth state of matter: In 2018, scientists aboard the ISS generated the fifth state of matter (in addition to solid, liquid, gas and plasma), Bose-Einstein Condensate (BEC).

BEC occurs when atoms are cooled to near-absolute zero and clump together, behaving like a single entity that exists between the physical world and the quantum world.

BEC was first achieved on Earth 25 years ago, but the microgravity and super-low temperatures of space make it exponentially easier to create and study them in an environment such as the ISS Cold Atom Lab.

They take less power to produce, and survive longer there, lasting for over a second, compared to a few hundredths of a second here on Earth. Why does any of this matter? Studying BEC, physicists believe, could be a key to unlocking new quantum technologies.