“Niki …Nanas…who?,” I’d initially asked when assigned this story. “Her name may not ring a bell now but I’m sure you know her! She’s the one who created those colourful sculptures of big, curvy women,” my editor replied. And true enough, I knew these figures that have been published in magazines and displayed in museum gift shops for decades: The voluptuous — often pregnant — female figures with plump breasts, large buttocks and small heads, painted in vivid colours, and captured in playful, joyful or simply triumphant poses.

To me, they underscore one thing: That a woman’s body — especially one that does not subscribe to societal, oftentimes patriarchal, standards of form and function — is a work of art.

Known as the “Nanas” — French slang for “bold, young chicks” — the figures are the trademark of the late French-American artist, sculptor and visionary, Niki de Saint Phalle (1930-2002).

And I had the opportunity to see them up close recently at the Schirn Museum in Frankfurt, which is currently exhibiting highlights of the artist’s diverse and extensive oeuvre. A large poster of a Nana with her hands joyfully thrown up in the air hangs at the museum’s entrance — the perfect antidote to an otherwise gray, drizzly February morning when I arrived.

Colour — lots of it — hits you as soon as you enter the exhibition hall. Even the walls were painted in an arresting ombre of vivid fuchsia, royal purple and intense cobalt, providing the perfect backdrop for de Saint Phalle’s works. (Also Read | Exhibition display modern art of South Asia through the lens of popular culture)

But first, an introduction

Born in 1930 in France to a US-American mother and French father, Catherine-Marie-Agnes Fal de Saint Phalle was a polymath who dabbled in painting, sculpture, film, and performance art with equal prowess.

A self-taught artist who had previously studied theatre, de Saint Phalle turned to painting after being hospitalized for a mental breakdown in 1953. After being discharged, she decided to pursue art more seriously, once saying, “Painting calmed the chaos that shook my soul.”

Much later, in 1993, de Saint Phalle revealed in her memoir “Mon Secret” (My Secret) that her father had sexually abused her as a child. This also cast new light on her works, be it the 1973 feature-length film “Daddy” (made with English filmmaker Peter Whitehead), in which she kills a father figure, or her free-spirited Nanas who thumb their noses at societal mores imposed on women.

“Men’s roles seem to give them a great deal more freedom, and I was resolved that freedom would be mine,” she once wrote.

Blasting gender boundaries with a .22

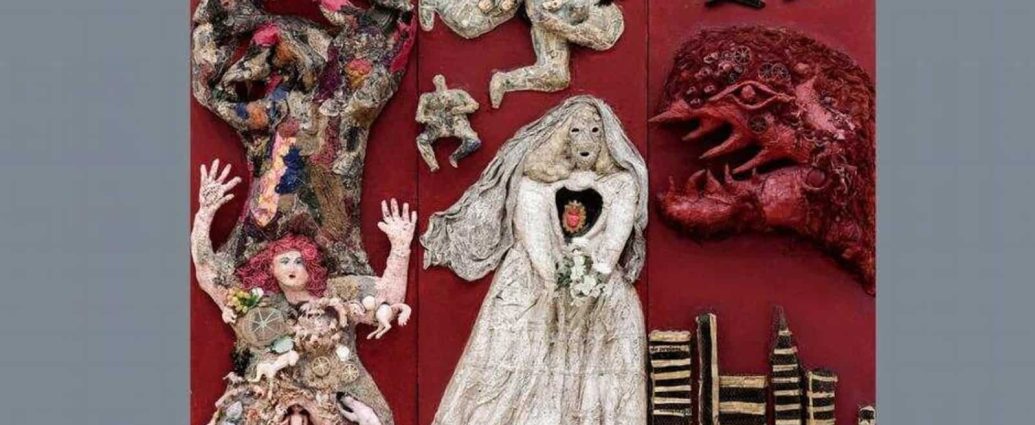

Often called a trailblazer in the world of modern art, Niki de Saint Phalle first rose to fame in the 1960s with her provocative “Tirs” or “shooting paintings” series.

To use today’s parlance, she went viral — without social media.

In front of live audiences, she shot with .22 caliber rifles or pistols at pouches of paint embedded within white plaster reliefs, causing explosions of colour to complete her works. She often invited her audience that included fellow artists to take the first shot, allowing them to actively interact with her works.

The statuesque de Saint Phalle, who’d also modelled and graced the covers of Life, Elle and Vogue, often wore a white jumpsuit while she “shot” her art. One of those jumpsuits is displayed along with her “bleeding” artworks at the Schirn exhibition.

Through her “Tirs,” de Saint Phalle broke down boundaries in a male-dominated art scene, sealing her reputation as one of the foremost women artists of her generation and earning the title “iconoclast” among admirers.

“She uncompromisingly defied the rigid social conventions of her time and the prevailing rules of the art world. Her artistic urge to create was fed by her rage against a society permeated by patriarchal structures, which she challenged with her openhearted, provocative work,” explained Katharina Dohm, curator of the Schirn exhibition, during the press conference.

Art in discarded items

Niki de Saint Phalle also created assemblages and landscapes using salvaged and discarded everyday items like broken crockery, razors, gloves and plastic objects like toy guns. Inspired by contemporary art, she experimented with different techniques, such as in “Nightscape” (1959), where she combined a dripping technique influenced by American expressionist Jackson Pollock and the ancient Moorish mosaic technique used by famed Catalan architect Antoni Gaudi.

Soon after, her works began exploring female identity. Though she did not actively participate in the emerging second-wave women’s movement of the 1960s and ’70s, her works nonetheless challenged women’s prescribed roles as wives, mothers and sexualized bodies in postwar Western societies.

Dawn of the Nanas

Inspired by her pregnant close friend, Clarice Rivers, she debuted her first “Nana” series in Paris in 1965, describing her larger-than-life figures as a “jubilant celebration of women.”

Originally made of fabric, yarn and papier-mache, these symbols of female virility not only exuded joy and strength but stood for a liberated matriarchy. She later used polyester — at that time a new material — for her Nanas to be weatherproof and robust enough to grace outdoor public spaces in cities around the world.

However, it proved to be a double-edged sword as her inhaling of polyester dust and other toxic fumes from work materials eventually led to protracted lung issues and death from respiratory failure in 2002.

Among her diverse Nanas, one could describe “Hon — En Katedral” (She — A Cathedral) as the “mother of all Nanas.” Working with Finnish painter Per Olof Ultvedt and her long-time partner and fellow artist Jean Tinguely, de Saint Phalle created it for the Moderna Museet in Stockholm in 1966. A smaller model of the reclining, pregnant Nana — through whose vagina visitors could enter and discover a milk bar and cinema, among others — can be viewed at the exhibition in Frankfurt.

Ahead of her time

Besides their feminist slant, Niki de Saint Phalle’s works also tackled socio-political issues. Her works like “AIDS, You Can’t Catch it Holding Hands (1986),” “Guns (2001)” and “Global Warming” (2001) respectively deal with AIDS stigmatization, gun violence and environmental neglect.

“Her work is still very relevant today. We are still dealing with equality issues between men and women. We are still having problems or issues about body positivity or shaming. We still have stigmatization of certain groups in the community. Her aim was that everybody should be living free,” said Kathrina Dohm.

And as for the Nanas with whom de Saint Phalle is most associated, Dohm concludes: “They tell women, ‘My female body is powerful… There’s no reason to be ashamed. No reason to hide.'”

The exhibition titled “Niki de Saint Phalle” runs through May 21, 2023 at the Schirn Kunsthalle in Frankfurt.