The five stages of grief look different when one is mourning a planet. There’s typically fear, frustration, anger, guilt and sorrow, says Panu Pihkala, an adjunct professor of environmental theology at the University of Helsinki with a special focus on eco-anxiety. “As with any expression of loss, there is much variation in people’s experiences.”

Typically, ecological grief is triggered by a tangible change in one’s immediate environment (such as the death of a glacier, river or reef), disruption of identity, or fear of future loss. From Inuit communities in Arctic Canada to wheat farmers in Western Australia, local populations are “struggling to cope, both emotionally and psychologically, with mounting ecological losses and the prospect of an uncertain future,” social scientist Neville Ellis of the University of Western Australia and climate scientist Ashlee Cunsolo of Memorial University of Newfoundland wrote in a report for the online platform The Conversation, in 2018.

This grief is now surfacing in a range of expressions. Funerals are being held for glaciers, with memorial plaques erected where they once stood. Songs are being composed for dying reefs. Art projects are taking giant chunks of icebergs and placing them in city centres, or livestreaming the sounds and sights of a glacier as it cracks and shatters a few hundred kilometres away.

“What’s new is the extent and scale of the sorrow over what is being acknowledged as irreversible loss,” Pihkala says. “So much is changing and so rapidly that the feelings of ‘ecological grief’ are very intense for some people, while others try to escape these feelings altogether.”

The facts are harder to escape. This year, Switzerland recorded its worst glacier melt rate since monitoring began more than 100 years ago. In Greenland, it rained (instead of snowing) in September. Across Europe, more than four million acres of land were destroyed by wildfires. Amid superstorms, super floods and mega droughts, the average annual temperature keeps rising, and Earth is now well on its way to the threshold of being 1.5 degrees Celsius warmer than the benchmark of pre-industrial 1850 levels — perhaps even by the end of the current decade.

***

The term “ecological grief” can be traced to the 1940s. Explaining it in his 1949 book A Sand County Almanac, American naturalist and author Aldo Leopold wrote: “One of the penalties of an ecological education is that one lives alone in a world of wounds.”

It is now recognised as part of the human response to the climate crisis, a spectrum of identified emotions ranging from climate despair to climate change depression, climate anxiety and ecological anxiety. In group cathartic events around the world, people are gathering to express and share these feelings. Among the earliest such events — if one doesn’t count the aboriginal events of centuries ago in the US, Australia and New Zealand — was a glacier funeral in Iceland in 2019, attended by 100 people, including local residents, scholars, scientists, tourists and the country’s prime minister, Katrín Jakobsdóttir. Glacier funerals have since been held in Switzerland, Mexico and the US.

On the UK’s Isle of Portland, an abandoned underground quarry and mine is being turned into a giant memorial for lost species. And since 2011, the Remembrance Day for Lost Species has used the hashtag #LostSpeciesDay to invite people to write, tweet, create art or frame poetry around extinct species, on November 30. This initiative, launched by British artist-activist Persephone Pearl, is timed to coincide with the United Nations Conference of the Parties or COP environmental talks, held at great environmental cost and to little effect each year.

“Remembrance as a discipline is important,” Pearl says. Even with it, “from generation to generation, people’s sense of what a normal or healthy ecosystem is, is changing.”

Meanwhile, from Goa to Canberra to Canada, artists are finding ways to visibilise climate change in cities, creating art, music and installations around dying mangroves, dwindling icebergs and bleaching coral reefs.

“We need more than scientific facts,” says Miriam Koshy-Sukhija, a founding member of the Earthivist Collective, which created a public art installation in a patch of dead mangroves in January-February. “As humans we are moved to act by stories, poetry, art and music, by a retelling of our personal experiences.”

.

GLOBAL EXPRESSIONS OF GRIEF

In black and white: Glacier funerals

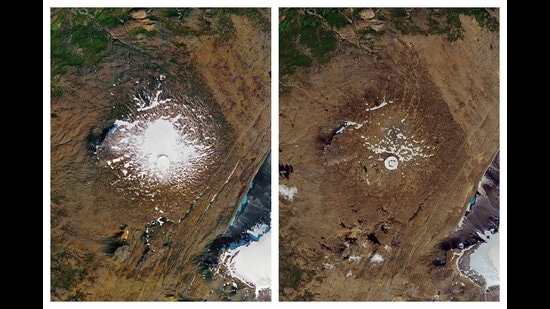

The Okjökull glacier was declared dead in 2014. It had stopped moving; it wasn’t regenerating.

It had been dying for a while. In the early 2000s, glaciologist Oddur Sigurdsson observed that new snow was melting before it could accumulate. The glacier that once sprawled across 16 sq km became Iceland’s first major one lost to post-industrialisation climate change.

Without the jökull (Icelandic for glacier), locals began to speak of changing the name of the area to just Ok. “There was a lot of emotion among the Icelanders,” says Dominic Boyer, an anthropologist at Rice University, Texas, and co-director with fellow anthropologist Cymene Howe of the 2018 documentary Not Ok. “We noticed that people felt lost as to how to grieve their loss. That opened up the possibility of creating a new ritual — or adapting an existing ritual — to grieve the loss of glaciers.”

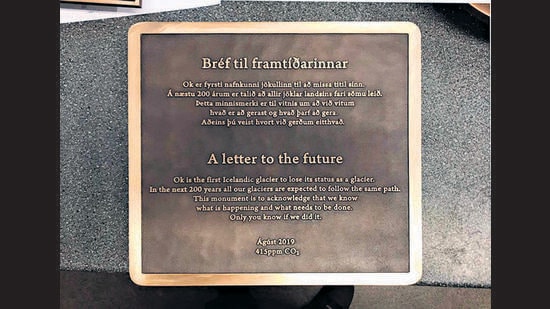

In 2019, a memorial ceremony was held to commemorate the death of Okjökull. About 100 mourners, including Sigurdsson and Iceland’s prime minister Katrín Jakobsdóttir, gathered to mount a bronze plaque on the bare rock that stood where it had once lain.

“In the next 200 years, all our glaciers are expected to follow the same path,” the plaque states. “This monument is to acknowledge that we know what is happening and what needs to be done. Only you know if we did it.” It is signed 415ppm CO2, a reference to the record high of carbon dioxide measured in the global atmosphere that May. This number has since risen; the current record is 420.99 parts per million, recorded in May 2022.

“As human beings we need to recognise losses in nature in order to understand, and to feel, the depth of those losses,” says Howe. Since the Okjökull memorial, there have been ceremonies to mark the deaths of glaciers in Switzerland, Mexico and the US. Local residents, scientists and other mourners have gathered, delivered eulogies, broken into song.

Switzerland had its first glacier funeral in 2019, when the Pizol in the Glarus Alps was declared dead. It had lost 80% of its volume in less than 15 years. In Oregon, scientists organised a funeral for the Clark glacier in 2020. A coffin containing meltwater from Clark was then delivered to the steps of the state’s Capitol building, an attempt at a wake-up call.

In 2021, in Mexico, scientists hiked 7 km to install a plaque similar to the one at Ok near the remains of the Ayoloco glacier, declared dead in 2018. Also that year in Ticino, Switzerland, hundreds turned up at the memorial for the Basodino glacier. It was declared dead after it was forced to retreat from over 1.5 of its 2 sq km area it had occupied 150 years ago.

“Scientists presented data, statistics, facts and figures. A Catholic priest said a prayer and sprinkled holy water at the site. A choir sang a farewell hymn,” says British author Nick Hunt, who attended the Basodino funeral. Hunt attended in all black. Attendees each carried a rock up the mountain, to build a cairn.

Like the remains themselves, “it was sadness wrapped up in beauty,” Hunt says.

.

Modern cave art: The Eden Portland Project

It’s easy to lose sight of how unique the fact of life is, until one remembers that nowhere else in the known universe has any other life form been found.

Even here on Earth, a whopping 99% of all life has, over the millennia, been wiped out. Through most of that time, the causes were varied: predators, evolutionary flaws, invasive species, natural disasters, inbreeding, low birth rates. In recent years, one cause has overtaken all others: human activity. Hundreds of species have disappeared. It’s hard to process the scale of this loss, so a new memorial hopes to render it visible.

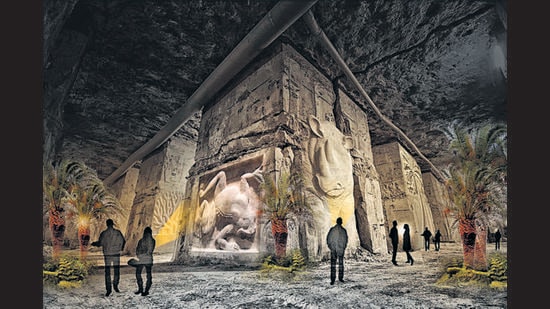

On the Isle of Portland in Dorset, England, an educational charity called Eden Project International is creating a subterranean monument called Eden Portland. In an exhausted quarry and abandoned mine, a series of underground galleries will chart the course of life on earth, using ancient carving and painting techniques.

“One of the evolutionary heroes we will be celebrating is the tiktaalik, the fish that walked, thereby pioneering the evolution of life on land,” says Sebastian Brooke, director of Eden Portland.

Above ground, the site will host a 30-metre-high installation designed by Ghanaian-British architect David Adjaye to resemble the Portland Screw, an extinct mollusc whose fossils have been found here. The installation will also depict 860 plant and animal species that have gone extinct in modern times, since the dodo disappeared in the 17th century, in etchings carved by sculptors from around the world.

Since Dorset is home to the Jurassic Coast World Heritage Site, considered one of the best fossil-collecting sites on earth, fossil displays will also be scattered across the subterranean halls.

“The ancient story of life is written in stone and in human hands stone is the medium in which we always sought to enshrine our deepest-held values,” says Brooke.

“Together we will tell the biggest story of all: the evolving story of life,” the website for the project states. “It’s a story four billion years in the making and so far as anyone knows is unique in the universe.”

.

Fast fade: Remembrance Day for Lost Species

On November 30, British author Nick Hunt held a small gathering in the garden of his home in Bristol, England. He was reading his short story, The Last of Many Breeds, about the thylacine of Tasmania. On Twitter, American poet Erin L McCoy posted poems inspired by the great auk. Dayton Martindale, host of the Storytelling Animals podcast, compiled six episodes featuring the Christmas Island forest skink, Bramble Cay melomys and dinosaurs, among others.

These are all creatures that went extinct over the past 200 years. Hunt, McCoy and Martindale were commemorating them on Remembrance Day for Lost Species (RDLS). For 11 years, around this date, groups have met to pay homage to species that have been lost and species on the verge of disappearing.

There’s been a dinner for the dodo in London, a remembrance ritual for the thylacine in Brisbane, a clown cabaret in France, and seaweed mandala-making session in Hawaii. Processions, dinners, readings, remembrance rituals, benefit concerts, even a bell-casting have been organised as memorial and awareness programmes, across Europe and in Fiji, Sri Lanka, Malaysia, Mexico and Japan.

RDLS emerged from a theatre project by Feral Theatre, explains member and artist Persephone Pearl, who is also co-director of ONCA, an arts, environment and social advocacy group based in Brighton. They devised a play called Funeral for Lost Species to express feelings of grief, futility and alienation around the UN’s Conference of the Parties or COP talks, in 2011

Emerging artists in Brighton were invited to create memorials for extinct species, which were placed around a graveyard in that city. This became the Celestial Garden of Remembrance for Lost Species. “One of the sculptures was in the style of a war memorial, with a list of names of species dead in the war on nature, and it got us thinking about remembrance as a discipline and the importance of recurring invitations to remember,” Pearl says.

Each year, events are now held around the world, unified by the hashtag #LostSpeciesDay. The website lostspeciesday.org lists some held from 2016 to 2020, with an interactive map marking events from 2013 to 2019, “but it’s tricky to know what participation is like now as it really is a decentralised initiative,” Pearl says.

The mission is evolving too. “We have shifted focus from single species to systems and interconnections,” Pearl says. “Since 2018 we have been espousing anti-racist environmentalism and working to uplift and centre black and POC, indigenous and queer perspectives. I think these shifts made it harder for some people to participate for a while, because of the conceptual challenges they posed, but I think we are seeing the benefits of the shifts with the emergence of more diverse organising and voices on and around the day.”

This year’s Onca programme on RDLS, for instance, was titled Queer(ing) Future Ecologies. “It explored approaches such as LARPing (Live Action Role Play), dark humour, and non-binary listening as approaches and strategies for the Anthropocene,” Pearl says.

.

Art: Tips of the iceberg

In India, Canada, Australia, England and the Netherlands, artists are creating monuments to climate loss and ecological grief. Recent projects have included scattering giant chunks of icebergs on London’s streets; creating a skeletal installation of dead trees in Goa; and broadcasting the sounds of a glacier cracking and breaking apart, in Calgary.

The Goa installation was called Mangrave: (En)circling the Loss, a public performance-art project set in a patch of dried-up mangroves along the newly expanded NH-66. “What has been destroyed is not just the forest but an entire habitat and a beautiful ecosystem,” says artist and activist Miriam Koshy-Sukhija. “And watching the deliberate destruction of these beautiful, highly resilient beings that have been such an integral part of the ecosystem of this place we call home was painful.”

Koshy-Sukhija is a founding member of Earthivist Collective, formed in February 2022 by a group of artists, musicians, filmmakers, scientists, academicians and environmentalists, as a way to process feelings of being overwhelmed, helpless and sorrowful about the destruction of their natural surroundings.

For the Mangrave project, conducted in January-February, the group created a spiral installation of scaffolding, covered in red prayer flags made of gauze. A plaster cast representing the spirit of the forest floated through it all in a boat.

“The idea was to question our role, evoke a deeper look at the ecological losses that are piling up at the altar of haphazard ‘development’,” says Koshy-Sukhija. “When trees are to be felled, they are marked in red. Leading the eye to the central spiral of prayer flags where the trees are draped in red was a way to remind people to question this destruction as they whizz past it along the highway.”

Meanwhile, in 2018, Danish-Icelandic artist Olafur Eliasson transported 30 blocks of glacial ice from Greenland and installed them in public spaces across London. They were left there on December 11, to publicly melt away.

Also in 2018, a permanent installation called Herald / Harbinger was created by Ben Rubin and Jer Thorp in Calgary, one of the fastest-growing cities in Canada. Here, the sounds of a dying glacier are broadcast live, via satellite, from a seismic observatory along the Bow Glacier about 200 km away, with audio and video thrown out across 16 speakers and seven large LED arrays. Cracks and shifts in the ice, louder in summer and muted in winter, greet office-goers as they walk through the square.

“It is a kind of rift in public space. You are at once at the edge of the ice of the Bow Glacier, and in the midst of tall skyscrapers filled with oil & gas company offices,” Jer Thorp wrote in a 2018 post on Medium.

.

Music: The Reef Grief song contest

“All the kaleidoscope of fish swimming

In and out the reef

There’s a time for hope and a time for grief

When you know this beauty will be gone.”

Australian contemporary folk singer-songwriter Karen Law’s song, Coral Coast, won the first Reef Grief Song Competition this April. His song tells the story of the loss of the coral ecosystem through the eyes of an old sailor and his grandson.

The Reef Grief contest was announced in September 2021 by Extinction Rebellion (ER), an activist group based in Brisbane. It called on musicians from around the world to compete to create music that could help communities process the loss of coral ecosystems. A prize of AUD 1,500 (about ₹83,000) was distributed among six winners (three songs tied for second place and two for third).

“We realised that without grief people tend to deny or overlook their problems including global heating,” says ER activist Rene Wooller. “Grief is a catalyst for change. Queenslanders must understand the reality that 1.5 degrees Celsius is no longer achievable. That our beloved reef will become dead or at least severely degraded. That many of the warm-water corals we know and love will become extinct.”

Some of the songs were surprisingly upbeat. Australian songwriter Andy Paine (above) used his ditty to tell a true, funny, insightful tale about visiting the reef with his mother, who is good at many things, but not too good at swimming.

“One Christmas Eve I was with my family / on the Capricorn Coast, hanging at the beach. / My mum says, ‘You know, that reef I’ve never seen, / I’d sure like to go before the whole thing is bleached,’” it goes.

“My songs are generally attempts to inspire listeners to create change, and when I thought about that the song flowed much easier,” Paine says.

All six songs were set to be played at a Day of Mourning for Dead Reefs event organised by Extinction Rebellion in March, but the event was put off amid extreme flooding in New South Wales.

Enjoy unlimited digital access with HT Premium

Subscribe Now to continue reading