In July, Marvel Studios president Kevin Feige announced the launch of Phases 5 and 6 of the Marvel Cinematic Universe, the most successful movie franchise in history. Phase 5 would begin with Ant-Man and the Wasp: Quantumania and the TV series Secret Invasion in 2023. Phase 6 would end with two Avengers films, …The Kang Dynasty and …Secret Wars, in 2025-26. “That will complete the second saga of the MCU, which is, of course, The Multiverse Saga,” Feige said.

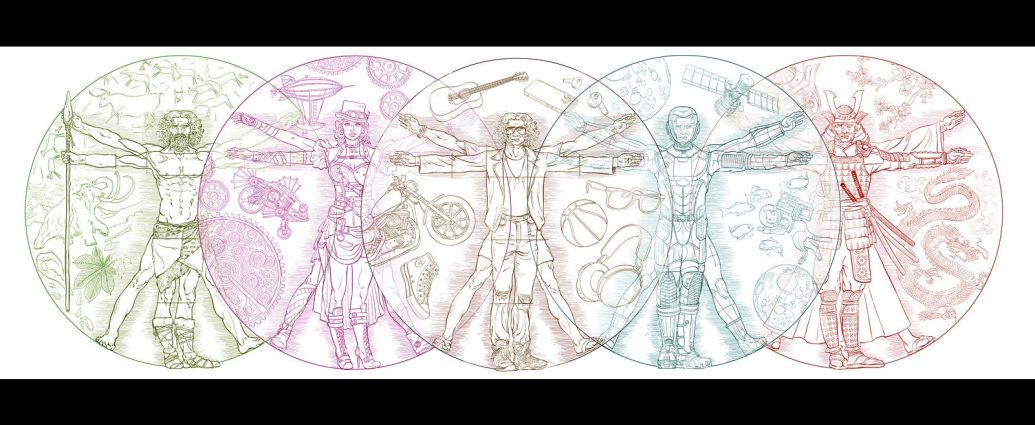

It seems like one can’t escape the multiverse these days. But the idea of it is hardly new. Universes running side by side have existed since human beings first began telling stories. The lokas of Hinduism and Buddhism, the nine worlds of Norse myth, Jannah and Jahannam in Islam and Heaven and Hell in Christianity, are all about worlds existing in parallel.

The current version of the multiverse came into its own in 20th century speculative fiction, when a middle-aged journalist named Barnstaple went on a motor holiday and drove through a portal into a parallel world, in HG Wells’s 1923 novel, Men Like Gods.

Since then, there have been numerous multiverses.

Wonder Woman crossed over to another world in the 1953 comic Wonder Woman’s Invisible Twin, and met her equivalent, Tara Terruna. Gardner Fox and Carmine Infantino reintroduced the concept — and created Earth-Two — in their seminal 1961 comic, Flash of Two Worlds. Over at Marvel Comics, in 1983, Alan Moore played with the idea of multiple universes in his Captain Britain stories in The Daredevils comic magazine.

Dungeons & Dragons’s city of Sigil, the city of doors, plays a similar role in tabletop gaming. Here, anything can be a portal to another world: a scrap of music, a memory, a disused archway, even a curse from its enigmatic ruler, the Lady of Pain. There are multiverses in any number of animated shows, from Ben 10 to Rick and Morty.

There are the versions of multiple universes colliding so beloved of fan-fiction writers – where Doctor Who could go adventuring with Sherlock Holmes and meet the Winchester brothers from Supernatural. Or Aang from Avatar the Last Airbender could meet Harry Potter and teach him to use energybending.

In his Dark Tower series of novels, Stephen King’s multiple worlds are centered on the titular structure, the one fixed point in all these worlds. In the first novel of the series, …The Gunslinger, a character talks about the nature of his universe — and, who knows, the nature of ours as well: “If you fell outward to the limit of the universe, would you find a board fence and signs reading DEAD END? No. You might find something hard and rounded, as the chick must see the egg from the inside. And if you should peck through that shell, what great and torrential light might shine through your hole at the end of space? Might you look through and discover our entire universe is but part of one atom on a blade of grass? Might you be forced to think that by burning a twig you incinerate an eternity of eternities? That existence rises not to one infinite but to an infinity of them?”

The theory of everything

But it’s not just speculative fantasists who have been fascinated by the idea of the multiverse. The 5th-century-BCE Greek philosopher Anaxagoras wondered if, just as there was a world for us, complete with cities and people and a sun and a moon, there were worlds for others. The 4th-century-BCE philosopher Chrysippus thought that the universe was destroyed and recreated all the time, a concept that the author Terry Pratchett had a lot of fun with in his Discworld books.

Among other things, Pratchett used a concept called Trousers of Time, a riff on an episode from an old BBC radio comedy series. The series was called I’m Sorry I’ll Read That Again; the episode, Professor Prune and The Electric Time Trousers. The Trousers of Time in Pratchett’s world are what are used, knowingly or unknowingly, whenever a choice is made. Each choice is a trouser leg, and in one novel, a character who makes a certain choice is given insight into what his life would have been like if he had picked the other one.

The Trousers of Time — the idea of one entrance and multiple exits — is the Discworld version of a serious and hotly debated theory of the multiverse, which began as a drunken idea. One evening in 1954, at Princeton University, the physics students Aage Petersen (an assistant to Niels Bohr), Charles Misner and Hugh Everett III, after some heavy sherry drinking, started discussing the paradoxes of quantum physics.

During the discussion, Everett, a voracious reader of science-fiction, came up with an idea that seemed to resolve a number of these issues; he posited that quantum effects cause the universe to constantly split. This became the basis of his PhD thesis, On the Foundations of Quantum Mechanics. The original dissertation was so dense that John Wheeler, his advisor, worked with Everett to make it more digestible.

Wheeler, a distinguished physicist who had coined the terms “quantum foam” and “worm hole” and a man Stephen Hawking called “the hero of the black hole story”, wrote that he “found (Everett’s) draft barely comprehensible. I knew that if I had that much trouble with it, other faculty members on his committee would have even more trouble.”

In simple terms, if we take the case of another famous thought experiment in quantum mechanics, Schrodinger’s cat could be alive or dead in its box. When the box is opened, the universe where the cat is dead splits from the one where the cat is alive. So, the universe of the unopened box has split into two, once the result is observed, and the observer in one universe has no awareness of the other universe created by the choice.

Everett was a fascinating character, a brilliant physicist who left academia, possibly following disappointment with the way his ideas were received — there was very little interest in his theories of quantum universes — and went on to work with the US Department of Defense on, among other things, the principle of mutual assured destruction after a nuclear war, and the application of game theory to the analysis of ballistic missile performance.

A committed atheist, he had asked that his ashes be disposed of in the trash. After he died of a heart attack at 51, in 1982, his wife kept his ashes in an urn for a few years, before complying with his wishes. In 1996, his daughter Elizabeth Everett, 39, died by suicide, saying in her final note that she wished her ashes to be thrown out as well, so she could “end up in the correct parallel universe” and meet her father again.

That poignant note may represent the core of the multiverse’s appeal. What if there is another universe where the ones we lost are still alive? What if there is a world where we said “No” instead of “Yes”? Took that chance? Made a different choice? Were wealthier, more successful, or happier?

What if?