Every detective story has the same components. The crime, the investigation, the disclosure. The motives are usually drawn from the same catalogue: envy, rage, greed, lust and, in the case of serial killers, gluttony. The detective is often an archetype – a loner, a flawed human, with psychological quirks that make their minds more agile, more analytical.

Which makes telling a truly innovative crime story that much more difficult.

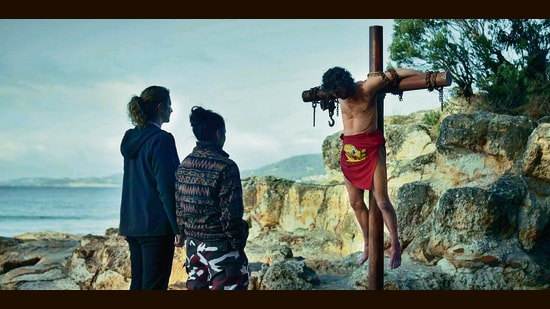

One sees the struggle play out on screens today: retellings of old stories featuring French detectives and luxury trains; or new ones featuring gizmos and time travel. Over and over, the same tales are retold. New twists are attempted, but fail to land (an island of women, a dead man on the beach… but then what? The 2023 series Deadloch simply finds nowhere to go.)

Why has it become so much harder?

Well, the crimes themselves have changed. Murder alone hasn’t been enough for a while.

In 1946, George Orwell published an essay titled The Decline of the English Murder. “Our great period in murder, our Elizabethan period, so to speak, seems to have been between roughly 1850 and 1925, and the murderers whose reputation has stood the test of time are the following: Dr Palmer of Rugeley, Jack the Ripper, Neill Cream, Mrs Maybrick, Dr Crippen, Seddon, Joseph Smith, Armstrong, and Bywaters and Thompson,” he wrote, adding: “In one way or another, sex was a powerful motive in all but two cases, and in at least four cases respectability — the desire to gain a secure position in life, or not to forfeit one’s social position by some scandal such as a divorce.”

Orwell was examining the shift away from the “murder for respectability”, contrasting killers such as Smith (a baker and bigamist who drowned three of his wives in the late-1800s) and Crippen (a mysterious doctor who killed his wife in 1910) with the earliest examples of the spree killing, which included the so-called “cleft chin murder” (so named because the victim had a cleft chin), in which an 18-year-old English waitress and a 22-year-old American deserter tried to kill two women and killed a taxi driver over a period of six days, in 1944.

The spree killing would feature, over and over, in headlines in the real world, and in fiction created through the 20th and 21st centuries.

Charles Starkweather and Caril Ann Fugate’s killing spree — the 19-year-old and his 14-year-old girlfriend killed 10 people, including her entire family, over nine days in 1958 — inspired the films The Sadist (1963), Badlands (1973), Guncrazy (1992), Kalifornia (1993), Natural Born Killers (1994) and Starkweather (2004); as well as the 1982 song Nebraska by Bruce Springsteen, a slew of books, and episodes on a number of TV shows.

Then this was no longer enough, and we got the mass murderers: sadists, school shooters, thrill killers, and now, social-media slayers who livestream their crimes and hold the viewer complicit.

A victim is lowered into a vat of acid, based on the number of likes that flow in; someone else is drawn across a rack. It is lurid, messy, and asks nothing of the viewer. When the law bursts in, it is often at least a bit unclear how they joined the dots. And one is left not with a wish to review the clues, but rather a sense of relief that it is over.

Death by tech

Technology is the elephant in the room.

How effective can a detective be, in a world of near-constant surveillance and AI-led profiling? How good can a detective show be, when the motive is as tawdry as a lurid desire for online fame (or notoriety)? And how skilfully can a tale be crafted, in a voracious entertainment industry that simply wants another season released?

Orwell called the murders for respectability, products of “a stable society where the all-prevailing hypocrisy did at least ensure that crimes as serious as murder should have strong emotions behind them”.

For better and worse (after all, stability is only ever stability for the lucky few, isn’t it?), no one would call ours a stable society.

And so, in place of the gentlemanly French detective and the masterful English sleuth, whose formulae all added up and whose science was always verifiable, we have shows such as Criminal Minds, in which it is likely a case would never be solved without Penelope’s fictional technology. We have the murderous and unreasonably attractive Dexter, which tells a most improbable tale, that soon spirals into sameness.

And yet we remain glued to crime fiction. Thrillers, mysteries and detective tales are the most popular literary genre, accounting for 32% of all book sales.

People engage with this genre for two broad reasons: to be shocked by the crime, or comforted by the idea of inevitable punishment. As it becomes ever-harder to shock, perhaps the way forward, for the murder mystery, is back, to a place of greater comfort.

A return to an age when “The murderer should be a little man of the professional class — a dentist or a solicitor, say — living an intensely respectable life somewhere in the suburbs, and preferably in a semi-detached house, which will allow the neighbours to hear suspicious sounds through the wall. He should be either chairman of the local Conservative Party branch, or a leading Nonconformist and strong Temperance advocate. He should go astray through cherishing a guilty passion for his secretary or the wife of a rival professional man, and should only bring himself to the point of murder after long and terrible wrestles with his conscience. Having decided on murder, he should plan it all with the utmost cunning, and only slip up over some tiny unforeseeable detail… With this kind of background, a crime can have dramatic and even tragic qualities which make it memorable and excite pity for both victim and murderer.” (Orwell again)

Of course, this would be easier in a period setting, and it would explain the lasting popularity of Sherlock Holmes and Hercule Poirot.