Forty years ago, when India was still a closed economy, Dr Prathap C Reddy set up the country’s first private, corporate hospital. The 150-bed Apollo opened on Greams Road, Chennai, in 1983. It was a gleaming, multi-specialty space built for comfort and state-of-the-art health care — very different from the functional trust-run and missionary-run hospitals of urban India then, and a world away from the rather dysfunctional, overstressed, understaffed government hospitals that most of the urban middle class avoided as if they didn’t exist.

Apollo Hospital offered imported technology and surgeries without wait times. At a time when Indians liquidated savings and borrowed to travel abroad for complex procedures, the first Apollo offered heart surgeries at one-tenth the cost of having them done in the US.

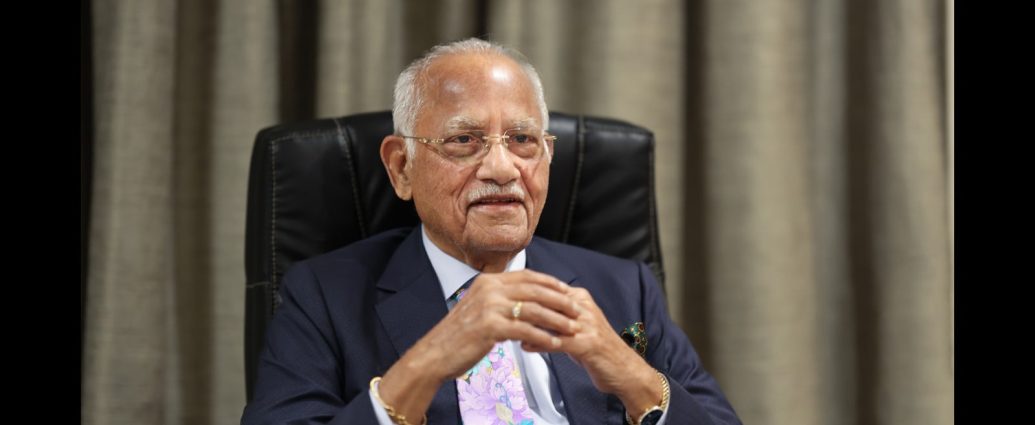

Dr Reddy is now 90 (he was born on February 5, 1933). His Apollo Group encompasses over 70 hospitals, more than 10,000 beds, and 400 clinics. The Group runs teaching facilities such as the Apollo University in Chittoor, Andhra Pradesh, and Apollo Buckingham Health Sciences Campus in the UK. As of last year, it has expanded overseas, running hospitals with local partners in Uzbekistan and Bangladesh.

Private health care, meanwhile, has expanded to numerous hospital chains and an estimated 43,000 private-sector hospitals, according to Statista. As the growing number of corporate hospitals deal with rising public distrust over inflated bills, quotas for doctors, and opaque collaborations with pharmaceutical giants, the legacy of privatised health care is a mixed one. But the story of how it all began in India is intriguing. There’s tragedy, pathos, lessons passed down from parent to child. And through it all, a man still in love with the power of medicine.

Dr Reddy, who remains chairman of the Apollo Group, still goes into the office six times a week; one of those days is reserved for a visit to the original Chennai hospital, to interact with patients, doctors, and other staff.

“God has given us extraordinary powers, and we should use some of them,” he says. “I think if you have a purpose, and if that purpose makes you happy, then that’s all you need. It’s difficult in health care, because you can’t save everyone. But if you know you’ve given it everything, you’ve not compromised on treatment or technology, and you are doing better every day, that should be enough.”

***

Reddy was born in the village of Aragonda, in Chittoor, Andhra Pradesh, to a farmer and a homemaker. His mother, he says, found joy in feeding people. “Everybody who crossed our door would be fed. I think I was brought up by great parents.”

By age 24, he and Sucharitha Reddy, the niece of a family friend, were married. By this point, Reddy had become the first person from his village to graduate.

He studied for his MBBS in Chennai before heading to the US for a residency in the 1960s, with his young wife. He went on to work at some of that country’s best hospitals, including Massachusetts General in Boston. He was living the high life.

“My father loved cars. Every time I bought a car, I would send him a picture,” Dr Reddy says. “In response, on one of my birthdays, he said that he and my mother admired what I was doing, but ‘suppose you did something for the country, how would that be?’”

Perhaps it was time to go home. The Reddys had four daughters by this time, but his wife encouraged him to make the shift. The family packed up and returned to India in 1971, where Dr Reddy began practising with a hospital in Chennai.

A patient he lost there would change the course of his life. It was a 38-year-old who had tried to raise funds to go to the US for a cardiac procedure but couldn’t meet the target in time. He died, leaving behind a wife and two children in shock.

“That’s when I said, how many more are going to die, and why should they,” Dr Reddy says.

He’d seen what Indian and Indian-origin doctors were doing in the US. Why not nurture some of that talent here? He began to lay the groundwork for Apollo. He envisioned it as an integrated super-specialty hospital equipped with imported technology and highly trained doctors, surgeons and support staff, that would be affordable and accessible when compared with the option of travelling abroad for comparable treatment.

Setting it up was not easy. One key challenge was the 360% customs duty on medical technology, which were considered luxury goods; another was getting a loan sanctioned — hospitals at that time were not eligible for funding from financial institutions.

Dr Reddy lobbied hard. “I must have made at least 100 trips. Every Friday morning I would go to Delhi to liaise with the bureaucracy, hopping from department to department, from undersecretaries to ministers, to the private secretary of the prime minister,” Dr Reddy says.

He finally met PM Indira Gandhi. “She heard me out and I had her blessing,” he says.

His efforts led to reforms. Crucially, the finance ministry, then led by Pranab Mukherjee, gave the go-ahead to loans for hospitals, and lowered the customs duty on imported medical equipment.

The first Apollo hospital was finally launched in August 1983. It offered, for about $5,000 (about ₹50,000 then), heart surgeries that cost Indians upwards of $50,000 to do in the US. “Nobody thought there could be a hospital in India which can give the same care as the best hospitals in the world,” he says.

Dr Reddy’s four daughters help him run Apollo now. Preetha Reddy, Suneeta Reddy, Shobana Kamineni and Sangita Reddy are executive vice-chairpersons and managing directors. “They have relieved me of 99% of my work, so I am allowed to think of the future,” Dr Reddy says. “And I am very hopeful.”

There are two aspects to the future as the nonagenarian sees it. First, hospitals around the country are serving not only the population of the country but the population of the world, via medical tourism. But perception in the West is that health care in India is “cheap”, a sort of low-price-variable-quality deal. “So a change in perception is necessary.”

Second, India can become a great global health care force with the potential to staff hospitals around the world. “When I was in the US, Irish nurses made up a majority of the nursing force. Today, there is immense demand for doctors, nurses, technologists the world over, and India is most suited to supply this.” The potential for employment, and for the Indian middle-class to expand, is immense, if this demand can be met in a planned, strategic manner, Dr Reddy says.

On the eve of his last birthday things came full circle when he met Prime Minister Narendra Modi to present his ideas for the future of health care in India. “I think birthdays come and go,” he says. “They say the 90th is very auspicious. I will use it to dream and build my vision into a larger one.”