On December 4, the G20 sherpa convened the first meeting of the Indian presidency in Udaipur to prepare for the grouping’s summit on September 9-10, 2023, in New Delhi. A leader-led mechanism with global reach, this influential body runs parallel to the formal global institutions born at the end of World War II. Although the G7 grouping of major industrialised countries dates back to their informal gathering (1973) following the formation of the Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC)’ cartel, their engagement with the developing countries in a North-South dialogue process finally culminated, through different stages, into the consensus-driven G20 summit mechanism signifying tight interconnectedness of the global economy impossible to be structured according to one country’s or a small group of countries’ interests. This realisation underlay the setting up of the Financial Stability Board of the G20 countries in the wake of the Asian economic crisis (1997-98) and its upgradation to the summit level when the 2008 global financial and economic crisis burst in full fury.

Comprising 19 countries and the European Union, the grouping represents 85% of the global Gross Domestic Product, 75% of global trade, and 66% of global population. Apart from Spain, a permanent invitee, and major international and regional organisations like the United Nations, International Monetary Fund, World Trade Organization and the Association of South East Asian Nations, each presidency also invites other countries and regional organisations of its own choosing. At its third summit in Pittsburgh, United States (US)) in September 2009, the leaders decided that it would be the primary forum for international economic coordination. It currently functions on the basis of a troika comprising the preceding, the incumbent, and the succeeding presidency – India, Indonesia, and Brazil currently – without a permanent secretariat; the troika system provides a certain continuity to the grouping’s policy direction whilst affording an opportunity to the incumbent to leave its imprint on its growth. Despite its origin, the congregation of influential national leaders had resulted in its agenda being widened from that of the purely economic and financial to other crucial aspects vital for national and global stability in politico-economic sense. Thus, it has the Finance Track, involving the finance ministers and central bank governors, for macro-economic framework, international financial architecture, sustainable finance, financial inclusion and international taxation whilst its Sherpa Track, involving personal representatives of the national leaders, covers common challenges in areas like agriculture, anti-corruption, culture, digital economy, disaster risk resilience, development, education, employment, environment and climate, renewable energy, health, trade and development, and tourism. Although not part of these two tracks, the G20 foreign ministers also convene prior to the summit to set the geopolitical backdrop for the leaders. To add a public participation dimension, there are several engagement groups covering sectors like business, civil society, labour, parliamentarians, science, audit authorities, start-ups, think tanks, mayors, women and youth.

The G20 process of decision-making and implementation involves consensus amongst the members based on prior consultations with the official agencies and entities involved in the two tracks which also receive feedback from the various engagement groups. As originally envisaged, the G 20 leaders’ communiqués are the norm setting for the concerned agencies and entities which further flesh out the broad directions set out in them; yet, the relevant international organisations comprise a much larger membership than that of the G20 where these broad directions, backed though they are by a very influential group within, have to be further negotiated into policy decisions. As a smaller grouping of leaders facing the collapse of the global economy in 2008, it provided the political will for massive reflationary programmes at home to regenerate recovery and to ensure adequate capital flows. Its early success was also in respect of benchmarks in national and international banking, exchange rate, trade practices, and reform agendas for the various Bretton Woods institutions. Yet, it is nowhere near realising the expectation, expressed by the then Prime Minister (PM) Manmohan Singh in 2008, of a “New Bretton Woods II”. Despite expectations, there was inadequate coordination in exit strategy for the national stimulus packages nor efficacious effort in national macro-economic balancing for the stronger global growth after that immediate threat had receded, a problem which dogs the G20 and the community of nations at large. For the last several years, financial vulnerabilities and deepening geopolitical tensions have greatly contributed to global economic instability further aggravated by the pandemic and the Ukraine conflict; the last two have spotlighted the national or narrower regional interests cancelling the overriding interests in addressing the far larger and pressing global challenges whose interconnectedness brought this grouping about in the first place. Instead, as the 2017 US National Intelligence Council global trends forecast through 2035 states, “financial crises, the erosion of the middle class, and the growing public awareness of income inequality” feed an anti-trade liberalisation and anti-globalisation sentiment in the West.

The mounting global challenges of heightened risk of recession, high national debt in major economies, manifestly crippling effect of global warming on physical and social infrastructure and inequality within and between countries, frequency of black swan events such as the pandemic, high energy and food prices, destabilising effects of international tension between major powers, the growing supply chain vulnerabilities arising from geopolitical and geo-economic shocks, international terror financing and other criminal networks, and the wider fraying of the global norms – in other words, red lines – make the task of the G20 leaders and the international community at large a daunting one.

As the global economic uncertainty shows no sign of easing up, conflation of simultaneous contributory factors further aggravates it: China’s unique zero-Covid policy, in response to the outbreak of this event, is further protracting its current economic slowdown caused substantially by this occurrence itself and causing jitters in the world markets. Although geopolitical factors have been recognised for quite some time for negatively impacting on the effectiveness of the G20 mechanism, the Ukraine conflict has nearly threatened to derail it. No joint statements were issued after the preparatory meetings of the G20 finance ministers as well as of the foreign ministers. A highly unusual – and political – formulation in the Bali summit Leaders’ Declaration, especially with regard to Ukraine, pre-empted the likelihood of the unprecedented outcome of the summit ending without one. The recent summit process has tellingly demonstrated the uphill task before the Indian presidency, and the following ones, for the grouping to be true to its founding vision.

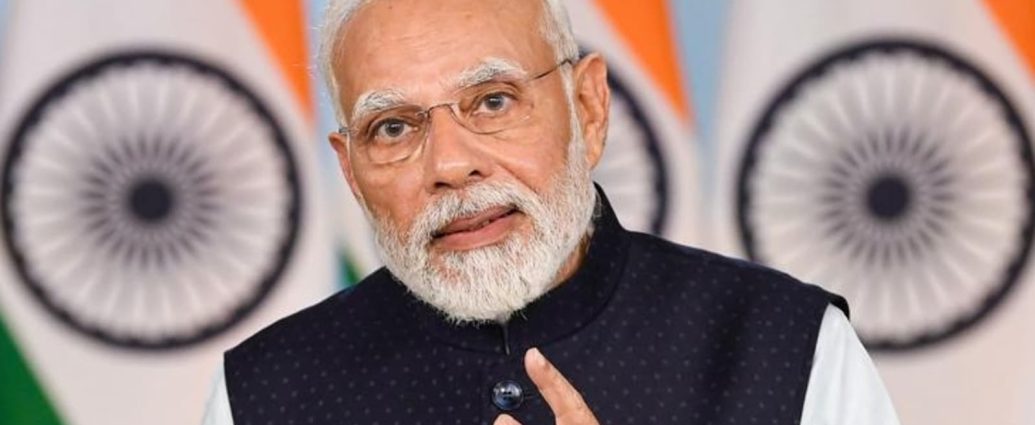

It is fortuitous that the current G20 troika comprising Indonesia, India, and Brazil represents the Global South to galvanise it. The Ukraine tragedy is troubling for humanity; sadly, for the residents of Afghanistan, Somalia and other hot spots in the Global South, it might not be too unfamiliar an experience. As PM Narendra Modi has said more than once, war cannot, especially in this century, bring any advantage in the face of the looming, potentially catastrophic global challenges which no country can manage single-handedly or escape from. Approaching these challenges in this perspective will moderate any self-serving calculations shaping the dynamics of the conflict situations in different parts of the world; on the other hand, this prolongation contributes to the political disarray within all stakeholder countries where ever they are. In other words, as he put it in a recent op-ed, giving up the zero-sum mindset would lead to ‘One Earth, One Family, One Future’. As a robust democracy and the fastest-growing large economy when the global economy is practically in a stall, several governance experiences can constitute the Indian G20 agenda for a more democratic and equitable global future.

Under the Indian presidency’s approach, scaled up digital technology can generate global impact in social protection, financial inclusion and electronic payments. Representing the wider Global South aspirations, sustainable socio-economic growth in harmony with the environment buttressed by suitable lifestyle changes, diplomatic activism to shield global supply chains for food, fertilisers and medical products from the geopolitical churn, and parallel conversations for mitigating the risks for weapons of mass destruction and enhancing global security would be the key thrusts of the Indian presidency. India has added start-ups and disaster risk resilience to the other engagement groups. There is, indeed, a civilisational complexion to this thought imprint drawing upon our traditions of inclusive dialogue and consensus building. These broader thematic directions would filter through the complex web of institutional and public diplomacy engagements to generate actionable roadmap for the September 2023 summit.

As the history of this grouping shows, not all ideas and initiatives under Indian presidency will lead to impactful results especially in the current geopolitical fraught situation. But the position papers and the wider public diplomacy surrounding it would make a significant contribution to the larger global discourse on the current challenges; continuation in the next troika and the succeeding Brazilian presidency would help in firmly embedding them in this discourse. Many initiatives may not require a multilateral adoption or huge capital outgo and can take a life of their own through transnational community level handholding and dissemination through this powerful platform. Challenges of capacity building, especially in the Global South, can be overcome to address risks in supply chains, capital outflow volatility, the weakened social infrastructure, localised impacts of global warming, and institutional fragility at local and, even, national levels which affect negatively political system stability. Dysfunctional institutions are a threat multiplier in themselves; according to one study, half of the world’s poor would be living in fragile or collapsed political systems by 2030.

Even as the G20 mechanism is a powerful instrument for India to make its thought impact on the ongoing, fractious global discourse on the current challenges, a stronger external media policy by the Indian government would help achieve it more pervasively. If the world has an interest in the India story, its telling cannot be left to others.

The article has been authored Yogendra Kumar, former ambassador.