As an author, I am often asked about my influences. Most of the names I mention are well known: George Orwell and German children’s book author Cornelia Funke, Weimar novelist Irmgard Keun and J. R. R. Tolkien as well Haruki Murakami, internationally renowned Japanese author and eternal Nobel Prize for literature candidate.

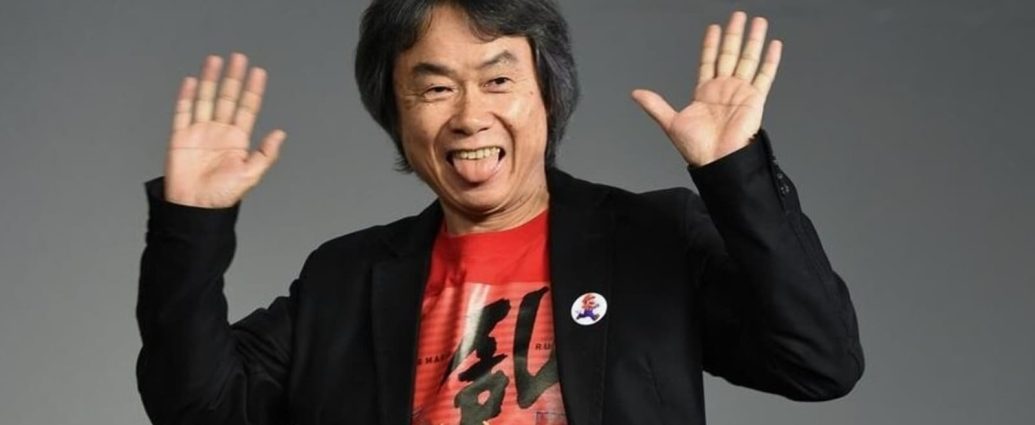

Only one other name invariably leads to raised eyebrows, whether at book events or during interviews or conversations with colleagues: Shigeru Miyamoto.

It’s good to be prudent with superlatives, but in the case of this man, nothing else will do: Shigeru Miyamoto, who was born on 16 November 1952 in Nantan City, Japan, is one of the most successful game developers of the 20th century. In 1977, the graduate of the Kanazawa College of Art started as a designer at the video game company Nintendo in Tokyo. Instead of realizing his dream and drawing mangas, Miyamoto spent three years designing cases for Nintendo’s video game machines.

Putting Nintendo back in the black

At that time, Nintendo had already existed for about a century, making card games, instant rice dishes, and toys. In the late 1970s, it invested a lot of money in a video game called “Radar Scope” — an arcade shooter similar to “Space Invaders” — to break into the lucrative US gaming market.

But “Radar Scope” flopped and Nintendo needed a replacement. After three years with the company, Shigeru Miyamoto was given the opportunity to design and develop not the case of an arcade machine, but the real thing: an entire video game.

The 28-year-old seized the opportunity — and propelled himself and his company to global fame with the invention of “Donkey Kong,” released in 1981.

With “Donkey Kong,” Miyamoto saved Nintendo from financial ruin and created three of the most enduring characters of 20th century pop culture: Italian plumber Super Mario, who can change his size with the help of mushrooms; his beloved Princess Peach with her pink dress and parasol; and the gorilla with the red tie named Donkey Kong.

The next coup: ‘The Legend of Zelda’

Shigeru Miyamoto has been developing games ever since, as well as directing the Nintendo Company from 2002 to 2020. He landed another coup when he invented the video game series “The Legend of Zelda” in the 1980s. In the “Zelda” games, the young hero Link has to rescue Princess Zelda and save the kingdom of Hyrule from the villain Ganon, short for Ganondorf. Many of the Zelda games are considered the best video games of their time, among them “Ocarina of Time” (released for the Nintendo 64) and “Breath of the Wild” (released on the Nintendo Switch).

Super Mario, Link and Donkey Kong: Today, Miyamoto has become the Stephen Spielberg of gaming — everyone knows his name, and among children his heroes are more popular than Mickey Mouse.

Even though they don’t speak, uttering noises or short phrases at most (Mario likes to shout “Mamma mia!,” while Link is completely silent), Miyamoto’s heroes have brought joy to children and adults all over the world for the past forty years.

I’m one of them. Growing up in the 1990s in the Ruhr Valley, a former coal producing region in the west German state of North Rhine-Westphalia with high unemployment rates, I projected myself into the fantasy worlds created by Miyamoto and Nintendo. Equipped with a Game Boy and a Super Nintendo that my older brother had bought, I found out as a young girl what it meant to save the world alongside Link, Mario and Donkey Kong. Miyamoto’s games helped me grow up believing I could do anything I set my mind to — and that it might even be a bit of fun, saving the world.

In his games, Miyamoto invented global heroes — they are all men, even if Link is just androgynous enough to inspire even a little girl like me — and redefined the meaning of the hero’s journey for the late 20th and early 21st century.

Fairy tales on the game console

In Ancient Greece and the European Middle Ages, being a hero still meant winning eternal glory in battle, as the “Iliad” and “Beowulf” tell us. In the Arthurian legends of the early modern era, heroes had to combine Christian piety and loyalty to their liege lord by facing and resisting countless temptations. In the process, the pleasures of life were sometimes neglected: the only Arthurian knight who finds the Holy Grail and immediately ascends to heaven is chaste Sir Galahad.

With Nintendo, on the other hand, saving the world is one thing, and one thing only: fun. Shigeru Miyamoto has created happy heroes and games that give us pleasure. His creations do not take themselves too seriously, in vivid contrast to the US superhero cinema of the Marvel and DC variety. If Super Mario has a companion in the world of books and films, it’s not Superman, but Alice who gets lost in Wonderland; Wendy, who travels with Peter Pan to the fantastic Neverland; and the poor woman with her pot of gold in British fairy tale “The Hedley Kow.”

Because ultimately, the Mario, Zelda and Donkey Kong games aren’t about superheroes and their moral or psychological dilemmas. They are not even about saving the world: What Miyamoto has done is transpose the modern fairy tale into the world of video games. In his games, good triumphs over evil, hope never dies, and saving and travelling the world is a whole lot of fun to boot. As a storyteller, he is and always will be one of my greatest idols. If you want to learn how to do a proper happy ending, don’t look to Disney or the Grimm brothers. Look to Shigeru Miyamoto.

On 16 November 2022, Shigeru Miyamoto turns 70 — and he has been keeping busy. As “representative director” of the Nintendo company, he has spent the past few years opening a Super Nintendo theme park at Universal Studios in Tokyo and working on a “Super Mario” feature film. Hollywood will be bringing the bearded plumber to the big screen: “Super Marios Bros” will be released in cinemas worldwide in spring 2023. Shigeru Miyamoto will then have every reason to look forward to his 71st year as one of the most gifted storytellers alive.

Edited by Brenda Haas