Before COVID-19, Prague was visited every year by millions of tourists looking for cheap beer and spectacular architecture. In the 1950s, on the other hand, the capital of then-Czechoslovakia attracted a very different crowd of travelers: Leftist intellectuals from around the world looking to see what life was like under socialism.

Many of those political tourists came from Latin America and included literary giants such as Jorge Amado and Gabriel García Márquez. Long forgotten, this shared history is now slowly being rediscovered and reassessed in the Czech Republic.

As the Cold War unfolded, both the West and the Soviet Union engaged in intensive propaganda efforts to demonstrate the superiority of their political and socio-economic systems, usually targeting audiences in Asia, Africa, the Middle East, and Latin America. And both sides saw art as one an effective way to relay this message.

In the USSR, the All-Union Society for Cultural Relations with Foreign Countries, or VOKS as per its acronym in Russian, had as its mission to invite public intellectuals and writers from all over the world to the Soviet Union and Eastern Bloc countries, about which they were encouraged to write.

Czechoslovakia, having joined the Eastern Bloc in 1948 after its Communist Party orchestrated a coup, was one of such destinations. Besides Jorge Amado and Gabriel García Márquez, the country received writers from Argentina (Raúl González Tuñón), Brazil (Graciliano Ramos), Chile (Ricardo Latcham, Pablo Neruda), Cuba (Nicolás Guillén), and Mexico (Efraín Huerta, Luis Suárez). Some traveled alone, others as part of larger delegations.

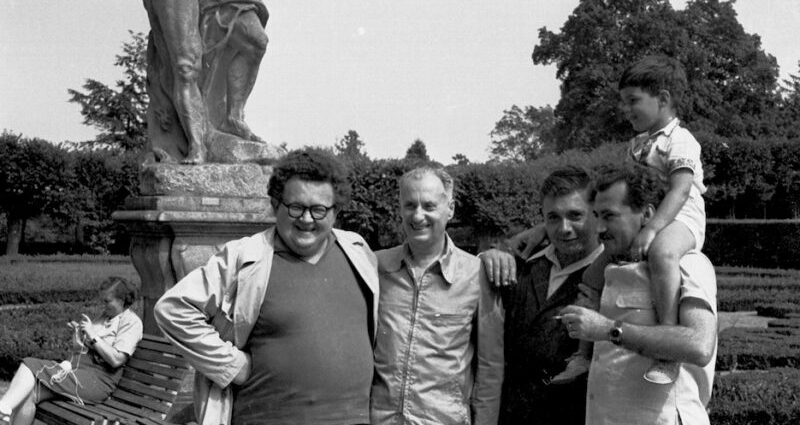

Prague thus became a cultural leftist hub from the 1950s onwards, gathering both burgeoning and established leftists writers such as Turkey’s Nazım Hikmet and the Soviet Union’s Ilya Ehrenburg.

Pablo Neruda, in fact, may have taken his artistic name from 19th-century Czech writer, poet, and journalist Jan Neruda (the Chilean poet was born Ricardo Eliécer Neftalí Reyes Basoalto). He never admitted this, but photos of him walking Neruda street in Prague, or posing before restaurants and pubs named “Neruda,” offers some solid ground for speculation.

Global Voices spoke to Michal Zourek, a Czech academic focusing on the ties between the Eastern Bloc and Latin America. Zourek, who authored the 2018 book “Československo očima latinskoamerických intelektuálů 1947-1959” (“Czechoslovakia in the eyes of Latin American intellectuals from 1947 to 1959″, which was also published in Spanish), explains what motivated those intellectuals to accept such invitations:

V Latinské Americe existovala celá řada autoritářských režimů, které pod záminkou potlačit levicovou subverzi masivně potlačovaly lidská práva. Proto latinskoameričtí umělci sympatizující s komunistickou ideologií dostávali z východní Evropy jistou materiální a morální podporu. Pokud jde o svědectví z těchto cest, tak texty ze čtyřicátých a padesátých let jsou obecně plné entusiasmu. Je videt, že na intelektuály z rozvojových zemí musely některé aspekty udělat velký dojem. Zejména pak kultura. Zmínky o vysoké kvalitě divadelních představení, zázemí škol a knihoven, jakož i velká sečtělost obyvatel, se v textech často opakují.

There were a series of authoritarian regimes in Latin America that massively repressed human rights, alleging the need to suppress leftist subversive forces. This is why Latin American artists in favor of communist ideology would get material and moral support from Eastern Europe. Regarding the testimonies of their travels, the texts written in the 1940s and 1950s are usually full of enthusiasm. It is clear that certain aspects [of socialist societies] made a big impression on those intellectuals coming from developing countries, particularly the state of the culture scene in Eastern Europe. There are many mentions of the high quality of theater plays, school infrastructures and public libraries, and the high level of people’s education.

Zourek goes on to explain how Prague and Moscow were a safe place for those intellectuals to make contacts and meet each other. “It wasn’t rare that famous intellectuals from Latin America met for the first time in Eastern Europe,” he said. “In their home countries, it wasn’t possible because the authoritarian and anti-communist governments in place simply wouldn’t allow it.”

Eastern Europe, Zourek says, played a crucial role for Latin American literature — if it wasn’t for the international communist movement, it is possible that the fabled 1960s generation of writers wouldn’t have been so influential, including in the West. “The works of engaged authors came out in enormous prints [in Czech, Polish or Russian], much higher than the ones in their mother languages, and all of this happened behind the Iron Curtain,” he said.

A land of plenty?

When visiting Prague or other places in Czechoslovakia, leftist intellectuals, who were mostly men, were treated like VIPs: They would stay in luxury hotels, have their expenses paid for and access to bilingual guides, receive writing honoraria, and eventually have their works translated into Czech or Slovak.

Those who were provided writing residencies would stay for long periods of time, notably in the Dobříš castle, the siege of the Union of Czechoslovak Writers from the 1940s to the 1990s. Some stayed even longer as they gained political asylum.

As Zourek explains:

Byly jim placeny cestovní výdaje a během pečlivě naplánovaného programu jim byl prezentován značně idealizovaný obraz místního života. Hosté na oplátku po návratu šířili pozitivní dojmy prostřednictvím cestopisů, článků a přednášek. Fenomén “politického turismu” byl důležitou součástí sovětské propagandy. Jednalo se o dlouhodobě plánovanou strategii, jejíž počátky můžeme hledat záhy po říjnové revoluci. Důležitou úlohu v ní sehráli právě intelektuálové, které Sovětský svaz toužil získat na svou stranu a následně je využít v ideologické bitvě.

They had their travel expenses paid for and during their very carefully designed travel program, they were offered to see only the most ideal aspects of local life. In return, the foreign guests would spread their positive impressions via travelogues, articles and conferences. This phenomenon of “political tourism” was a key component of Soviet propaganda, a well planned strategy that started immediately after the 1917 Russian revolution. A major role was assigned to intellectuals that the Soviet Union wanted to have on its side to use them later in its ideological struggle with the West.

One interesting exception in this idealized vision and description is Gabriel García Márquez, the Colombian Nobel laureate in literature who visited Eastern Germany, Czechoslovakia, Poland, Hungary and the USSR in 1955 and 1957. He did so partially on his own, and when officially invited, found ways to escape the official program to enquire by himself. In his book,”De viaje por Europa del Este” (“Journey Through Eastern Europe”), his descriptions of Eastern Europe are much more nuanced.

In the first chapter, Garcia Marquez describes Eastern Germany in unflattering terms, as in this scene where García Márquez enters a restaurant for breakfast: “What people had for breakfast would be the equivalent of a full meal in the rest of [Western] Europe, and would be much cheaper. But those people looked destroyed and bitter, and ate enormous portions of meat and fried eggs without any joy.”

In another chapter about Moscow, he writes about the taboo topic of Stalin’s cult of personality, quoting his Russian guide who says: “If Stalin was still alive [he had been dead since 1953], we would have a Third World. Stalin was the bloodiest, the most rancorous and most egomaniac figure in Russian history.”

For Czechs, a rediscovered heritage

In Czechoslovakia, communism ended in the fall of 1989, and in the successor states of Slovakia and the Czech Republic, the socialist past is usually regarded as a dark period of human rights violations, travel restrictions, and forced obedience to Moscow.

Such view colors Czech and Slovak historians’ approach to the leftist intellectuals who visited the country during those times. As Zourek, who studied in the Czech Republic and in Argentina, notes:

Během mých univerzitních studií jsem sice zaslechl zmínky, že v Československu pobýval Pablo Neruda či Jorge Amado, ale neměl jsem představu, že se jednalo o fenomén tak výrazný. Jinými slovy, že intenzivní kontakty mezi oběma regiony existovaly již před kubánskou revolucí. Roli zde možná hraje určitý despekt k těmto autorům. Mnozí na ně nahlížejí jako na idealisty či užitečné idioty, kteří svou návštěvou vyjádřili sounáležitost s režimem, který se neštítil násilí a perzekucí. Celá problematika je ale mnohem komplexnější.

During my studies in university, I heard a few mentions about Pablo Neruda and Jorge Amado spending time in Czechoslovakia, but I had no idea that this was such a deep phenomenon, that both regions had such contact even before the Cuban Revolution [1959]. This is perhaps due to the scorn with which those authors are now held [in the Czech Republic and Slovakia]: many consider them to be idealists or useful idiots who, with their visits, supported regimes that engaged in violence and persecutions. The issue is of course much more complex than that.

While those authors have long been celebrated in their home countries in Latin America, their legacy is only now resurfacing in the Czech historical discourse. García Marquez’ travelogue was translated to Czech for the first time in 2018 (“Devadesát dnů za železnou oponou“), while the others remain largely unknown.

Zourek shares his personal experience to explain why the process of reassessment is so challenging:

Krátce po střední škole jsem navštívil Chile, kde univerzita byla plná sovětských vlajek, portrétů Lenina, v knihkupectví se prodávala díla Marxe a Engelse. Myslel jsem si, že ta ideologie je mrtvá, nechápal jsem, jak někdo může obdivovat zločinnou ideologii, která omezovala svobodu slova, bránila lidem studovat, realizovat sny. Tento antagonistický postoj obou regionů ke komunismu je primárně dán zcela odlišnou historickou zkušeností. Proto se domnívám, že při hodnocení komunismu je třeba se oprostit od rodinné anamnézy, která mnohdy brání vidět tento transnacionální fenomén v jeho mnohobarevnosti. Tento přístup mi bohužel stále u mnoha českých historiků chybí. Myslím, že není náhodné, že politika komunistického Československa ve třetím světě se těší většímu zájmu v zahraničí nežli mezi českými badateli. Teprve v posledních letech se to začíná měnit a myslím, že to do určité míry souvisí s postupným vystřízlivěním české společnosti z antikomunismu. Věřím, že v následujících letech vznikne řada prací, které poukážou na to, že komunistické Československo dělalo v rozvojovém světe obdivuhodné věci, na které se nepodařilo po roce 1989 úspěšně navázat. Například na poli kultury.

Soon after secondary school, I visited Chile, where the university was full of Soviet flags, portraits of Lenin, where bookstores would be selling the works of Marx and Engels. I thought that ideology was dead, and couldn’t understand how anyone could admire a criminal ideology that limited freedom of expression, prevented people from entering university, fulfilling their dreams. This antagonistic position of both regions in regard to communism is due mostly to very different historical experience. This is why I think that when we assess communism, we have to separate ourselves from our family experience and history, which often doesn’t allow us to see this transnational phenomenon in its full diversity. Unfortunately, that dissociation is still not happening for a lot of Czech historians. I don’t think it is surprising that people in the developing world have more interest in the policies of Communist Czechoslovakia than their peers in the Czech Republic. It has began to change a bit in the past years, and I think this is thanks to the gradual reassessment of the communist period by Czech society. I believe that in the coming years we will see a series of works showing that communist Czechoslovakia did remarkable things in the developing world, which were mostly abandoned after 1989, for example in the area of culture.